If it’s fall and you fish, it’s time to be on the Rio Grande enjoying a warm sunny afternoon chasing hungry trout on the state’s big river.

“It’s the optimal time of year to be fishing the Rio Grande and its tributaries,” says Van Beacham, a longtime Taos area guide and author of “Flyfisher’s Guide to New Mexico.” “The weather is ideal, there’s not too much wind, it’s sunny and warm and the fish are active, trying to fatten up for the winter.”

And unlike much of the fishing season when fishing is best in the morning and evening, fall fishing is best done later in the day when the water has warmed up and the bugs come out.

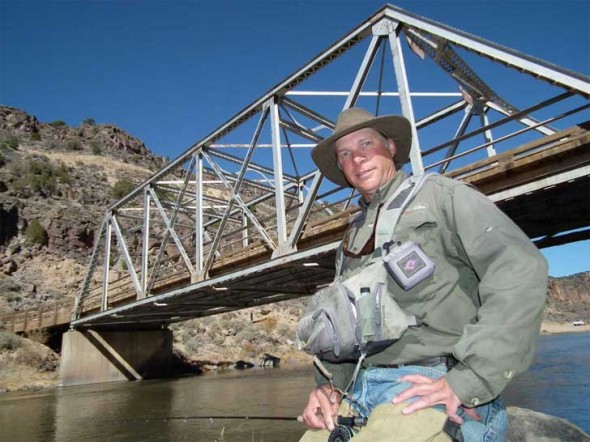

“It doesn’t get any better than this,” says Beacham, 52, of San Cristobal, as he shares some fall fishing tips during a recent outing to the John Dunn Bridge on the Rio Grande just north of Taos.

Beacham comes from a long line of “fishing bums” and has been showing his clients the trick to fall fishing since he opened his first guide and fly shop in Red River back in 1983.

Beacham says the Rio Grande is most productive when fished with a streamer or spinning lures in the fall as these potentially bigger meals are much more appealing to hungry fish.

The Rio Grande, a big river lined with volcanic rock, is notorious for skunking anglers who fish it with traditional flies and nymphs.

And that’s because the fish have so many hiding spots down among the underwater rocks that getting their attention with such a small lure can be extremely difficult.

However, a twitchy streamer or flashy spinning lure is more apt to be seen and chased by hungry trout in the Rio Grande, Beacham says.

Beacham says there are no real rules to streamer fishing, the lure can be fished upstream, downstream or across with a fast, slow or balky retrieval. It can even be jigged along the bottom with an up and down motion.

“The key is to keep it moving and the rod tip low to the water,” he said. “And never stop retrieving until you can see the lure, it’s amazing how many times a fish will follow it right up to your feet.”

Streamers like wooly boogers and sculpzillas in olive and black and sizes 2 through 8 are good to have on hand and a good rod for the Rio Grande is a nine-foot, five or six weight.

When casting these bigger lures fly anglers need to adjust their technique to accommodate the extra weight. When retrieving the line, the angler strips it in with short bursts at various lengths using the free hand.

Strikes will be fast and hard and setting the hook requires an additional strip of the line, Beacham says.

The Rio Grande supports wild rainbow, brown and cutbow trout that reach sizes up to 20 inches or more, Beacham says. And pure strain Rio Grande cutthroat, trout have also recently been reintroduced to the river in an attempt to reestablish the state fish in its traditional, native, habitat.

Beacham advises those venturing down to the Rio Grande at locations such as Pilar, the John Dunn Bridge and the Wild Rivers Scenic area above Questa to avoid wearing felt-soled wading boots because of the slipperiness of the riverside rocks.

Anglers need to drink plenty of water, carry some basis survival needs such as matches, a space blanket and energy bars. They should dress in layered clothing such as a fleece jacket and a nylon shell and let someone know where you’re going as these are remote and potentially hazardous areas.

Those seeking a quieter afternoon’s angling might want to pass up the streamers and stick to nymphs and dry flies on any number of creeks feeding the Rio Grande that also fish well in the fall, Beacham says.

Streams like the Arroyo Hondo, the lower Red River and the Cimarron below Eagle Nest Lake all offer anglers good fall fishing for feisty trout on traditional tackle such a 8-foot, four weight rod armed with a short leader and a couple of flies.

Beacham recommends using a mayfly nymph tied up like a gold-ribbed hare’s ear, but in olive instead and without the gold rib. The fly can be rigged with a bead head or flashback in sizes 12 through 22.

Hung below an attractor pattern, such as an egg or worm, this can be a deadly combination when dead drifted through a pool or riffle.

And if bugs begin to hatch on the water then a size 18 to 22 olive colored or parachute Adams dry fly will usually suffice to attract a surface strike from a hungry trout most fall days, Beacham says.

Beacham says when anglers are failing to catch fish with nymphs, most of the time it’s not the fault of the fly but the size of the weight and the length to the indicator.

The nymph should be bumping along the bottom and if it’s not, either the weight should be increased, the strike indicator moved up or a combination of both. If the fly is dragging then the opposite would apply.

Successful nymph fishing requires a dead drift and good line control and one means of achieving that it to learn to high stick, a method Beacham spells out along with numerous other tips in a section of his book called Small Stream Techniques.

Beacham’s book, the second edition of which was just released with updates and a new section on pike fishing on the Rio Grande, is comprehensive in providing not only detailed information of where, how and when to fish New Mexico’s many different waters but also in providing important tips on what gear to use, additional equipment and handy packing lists.

When he’s not out fishing Beacham, who is single, enjoys dancing to western swing music and taking in the diversity of Taos’ music and restaurant scene.

Born one of three brothers and a sister to William and Jo Ann Beacham of Santa Fe in 1958, Van Beacham says he was warned as a teenager that he was doomed to be yet another one of the Beacham family’s notorious fishing bums.

“My dad warned that I’d better find a way to make some money doing it cause that’s how I was going to end up,” Beacham says.

Beacham’s great grandfather, William Beacham, was the first to sell fly fishing tackle from his hardware store in Santa Fe and sired a son who became a notorious fishing bum.

Another one of his elders, John Bengard, was the superintendent of fish hatcheries in New Mexico and designed the Lisboa Springs trout rearing facility near Pecos, Beacham says.

His grandmother was the trout hatchery superintendent’s daughter and his grandfather the fishing bum born to the hardware and fishing tackle store owner.

Beacham credits his dad, who also loved to fish, with teaching him the solitary sport at an early age.

“My earliest recollection of fishing is of him sticking a bamboo pole in my hand, a worm dangling in the water and telling me not to move,” Beacham says. “This was somewhere up on the Rio Grande.”

Later as a teenager living in Pecos where his dad was working with the state highway department, Beacham found himself frequently fly-fishing on the Forked Lightning Ranch, now in the hands of the National Park Service.

Beacham attended the Vo-Tech high school in Santa Fe where he was schooled in electronics, graduated in 1976 and first worked at Eberline Instruments, one of Santa Fe’s few industrial businesses in the factory now standing empty on Airport Rod.

Beacham tried attending an advanced electronics school in Arizona but bailed after a few months and found himself in Jackson Hole, Wyo., working as a dishwasher, shuttle driver and finally a fishing guide.

Upon his return to New Mexico his dad cashed in a life insurance policy he had taken out on his son, the fishing bum, and loaned him the money to start up his first fly shop and fishing guide service.

Beacham now provides guide services throughout northern New Mexico, southern Colorado and Wyoming and also offers membership in his private fly fishing club with leased access to private waters in all three states. See his website at www.solitaryangler.com for more information.